Peace briefly breaks out in 1802. The scene is set for the Napoleonic Wars proper.

The blessings of total peace were only enjoyed for fourteen months, but it was almost three years before a full scale continental war again broke out. The causation of the renewal of the struggle is a complex subject with many roots going back to 1789 and beyond, but the most immediate reason was the mutual dissatisfaction felt by all the signatories of the peace agreements of 1801 and 1802. In fact, these amounted to little more than temporary truces, for the real issues of the struggle had not yet been resolved. - David Chandler

A brief peace broke out at the end of the Wars of the French Revolution and before the beginning of the series of titantic struggles we call the Napoleonic Wars.

This pause gets little attention.

It is seen as an uneasy truce. An unstable truce of exhaustion that inevitably led to the wars necessary to stopping Napoleon.

Necessary wars because Napoleon in his insatiable thirst for conquest, and inability to recognize any limits, could not be stopped anywhere short of the conquest of Europe, maybe the world, by anything else other than force.

Given his command of France's resources and his own genius generating that force required not just the mobilization of all the rest of Europe against him, but significant reforms to increase the efficiency with which that force was generated, and an unprecedented degree of co-ordination in its use. And with all that it took a number of significant mistakes on Napoleon's part (Spain, Russia) to give the Allies the final victory.

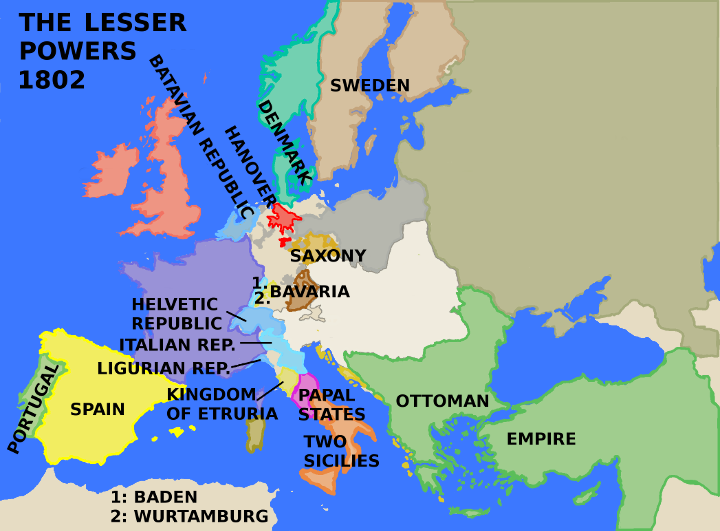

Note: The Two Sicilies, the capital of which was Naples, was also known as the Neapolitan Kingdom and its citizens and soldiers as "Neapolitans". Similarily the Ottoman Empire is sometimes referred to as Turkey and its armies and citizens as "Turkish" or "Turks". Also if it's not obvious the "Batavian Republic" is a renaming of the Netherlands, and the "Helvetic Republic" one of Switzerland. They had Republican governments usually considered to be French puppets at this time. Hanover had the same King as Britain but in theory (one Napoleon lent little credence) was an separate independant political entity.

In many ways although the allies nominally won the war, the ideals of the French Revolution and Napoleon's reforms of France won the following peace.

To win the war the allies had to remake themselves at least partially in France's image.

That those wars were Napoleon's fault is one, admittedly rather simplified, point of view. One popular in Britain, Russia, and the German speaking successor nations to Prussia and Austria.

The French (and some others) seem rather inclined to think Britain's determination to assert commercial hegemony over the world, including Europe itself eventually, and their implacable hostility to French power as embodied in Napoleon as what made the wars inevitable. It was British gold that enabled the reactionary powers of Russia, Austria, and Prussia to oppose the forces of modernity represented by Napoleonic France for so long.

In any event both points of view see the details of this peace as being of little interest given its aberrant and temporary nature.

They hold it's a confusing period from which nothing fundamental can be learned.

I disagree with this.

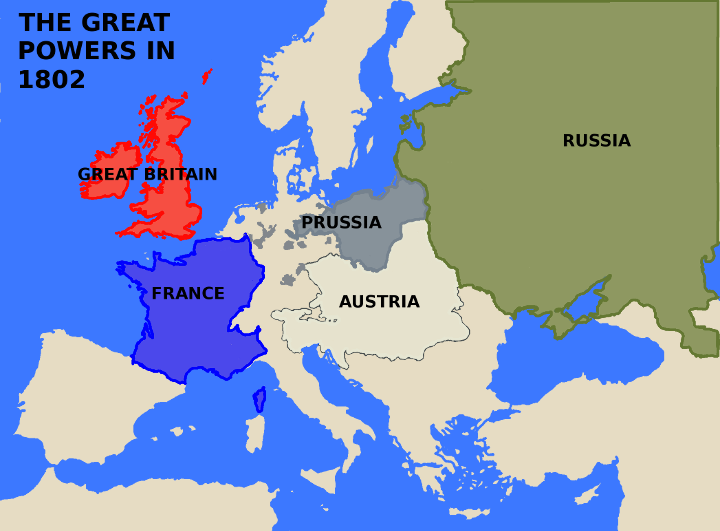

There's little doubt that the Great Powers of Europe, Britain, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia were rivals in significant ways. There's also little doubt that the peace agreements of 1801 and 1802, those of Luneville and Amiens, did not fully resolve the issues at stake.

This is not to say, just the same, that the leaders of those powers wanted war not peace. It is not to say that peace wasn't possible. It's not to say war was inevitable.

Why the world got war not peace is an important question. It is also a fruitful one.

The wars of the late 18th century had been tremendously expensive, and for most of the continental powers destructive too. The people of all countries (where they counted) were throughly tired of war. As were their leaders who feared the destruction of their states under the strain. By and large they saw continued war as costly and dangerous, and unlikely to produce results commensurate to its costs and risks.

The evidence is that Europe's leadership on all sides wanted peace if they could somehow procure it without sacrificing vital interests.

The story of the peace that ended in the Napoleonic Wars is one of how Europe's heads came to the conclusion they could not avoid war despite its undesirability.

In essence the Peace of Amiens between Britain and France was overly lop-sided in France's favor. Stringently interpreted it allowed Britain none of the colonial gains it'd won while letting France off the hook for its losses. France was once more allowed to be a significant world wide competitor in trade and colonies. The British had hoped for renewed access to Europe's markets as compensation.

Ever the grasping opportunist Napoleon took full advantage of the letter of the agreement without acknowledging British concerns for a more equitable final settlement. In response the British renewed the war with little or no warning, and catching the French off guard effectively swept them from the seas. This destroyed what ever small amount of trust might have existed between the British and the French.

With the British now dominant on the sea, and the French on the land there was little substantial they could do to each other. Napoleon's efforts to strike back at the British, both in character and likely necessary for reasons of internal reputation, progressively alienated and worried the continental powers especially Russia until finally Russia was able to form an anti-French alliance with Austria. The Third Coalition and the true start of the Napoleonic Wars resulted.

If at some point any of the powers had been able to fully understand the interests and preceptions of the others they might have been able to have cut a deal that allowed for ongoing peaceful rivalry within reasonable boundaries.

Instead the various actors came to see each other as predators that could not be trusted to keep agreements.

The Allies and Napoleon saw each other as existential threats that could not be negotiated with only fought against.

And so war, so clearly undesirable, came to seem unavoidable.

A lot happened in this period, and in parallel, to keep events straight here is a timeline.

(*)Note: Military operations take time. Pinning them down to a specific date is sometimes arbritary. For instance the Prussian occupation of Hanover was first ordered sometime in March, troop assembly in Prussian took some time, and then the occupation itself, even in the absense of opposition, took from March 30th to April 9th, different places being reached by the various Prussian agents and forces at different times.

It's also worth noting at this point that just because something happened at a specific date doesn't mean all the actors were aware of it on that date. It often took weeks for information to travel between the courts of Europe. Generally the fastest news could travel was the speed of a courier on horse.

The year 1799 saw the Directory restore a desperate situation for French arms. They were considerably helped by Allied fumbling and the subsequent defection of Russia from the Second Coalition.

Nevertheless Bonaparte who became First Consul at the end of the year faced a serious military situation with the new year of 1800.

With his customary energy and boldness, as well as luck, he soon restored the situation.

After the battles of Marengo and Hochstadt in June of 1800 it was mainly British finance and encouragement that kept Austria in the war, but not exactly fighting.

As Bryant writes "[o]n July 21st 1800, an Austrian plenipontentiary arrived in Paris to discuss peace" with the result that "the First Consul prevailed upon him to sign formal preliminaries giving France everything she had won by the Peace of Campo Formio three years before". But the Austrian leadership "refused to ratify terms based on an agreement dictated when the French armies were at the very gates of Vienna."

The British had also made a major subsidy dependant on Austria remaining in the war until February of 1801.

"Accordingly on August 15th Austria notified France of her inability to ratify the Paris preliminaries or to make peace without England. At the same time she expressed the readiness of both countries to negotiate separately. "

Truces in both Italy and Germany held until the end of November.

The critical background for this was a classic struggle between Britain as a dominant naval power and France as a dominant land power.

This struggle on the peripheries, necessarily indirect, and often ineffectual, was nevertheless quite serious.

The trade of Russian, Denmark, and Prussia might seem uninteresting, and the possession of Portugal, Copenhagen, Malta or Egypt less than critical, but in fact they were parts of a struggle for control of Europe's, and therefore the world's commerce. A struggle for global naval supremacy and therefore of the globe itself.

The grain and naval supplies of the Baltic region were essential to Britain's continued survival and also necessary components of any possible French naval revival.

Control of access to colonial commodities and of access to the markets for them meant a huge financial advantage that could be, and arguably was, decisive in determining the outcome of the struggle between France and Britain.

France had to have an army whereas Britain could concentrate on its Navy. Added to that advantage was the geographical fact that Britain lay across France's access to the Atlantic trade routes.

In the Mediterranean, however, a sea surrounded by, and restricted by, land and furthermore one France was closer to a more equal struggle was possible. Eygpt might potentially provide many colonial commodities that couldn't be produced in Northern Europe. Also control of the Mediterranean held out the possibility of re-opening a shorter more direct route to India and the Far East.

And the first stepping stone to Egypt and the East was Malta.

The British and French struggle over Malta wasn't a trivial sticking point. It was key. It was a strategic prize of high value.

In hindsight, especially after Nelson's victory of the Nile in Aboukir Bay, it might seem the British held the decisive edge in this competition.

Maybe not. Certainly at the time it didn't seem so clear. Despite her naval and financial advantages Britain as a whole was on the ropes.

Of the available historians Bryant may not be the best source regards diplomacy and doesn't even cover our entire period, but he is excellent on the stresses the British were feeling at this time.

"[B]y restricting the flow of certain essential commodities, the war had created shortages in real wealth which had fallen almost exclusively on the poor. By further contracting vital imports by an extension of his continental blockade to the Baltic, Bonaparte intended to strike at the stubborn rulers of England through the bellies of the poor."

Britain suffered a series of failed harvests. "By October [1800] the people in many districts were literally starving. A succession of bread riots, aggravated by the repressive measures of narrow-minded 'anti-Jacobin' magistrates and judges, brought home the danger in the situation. To keep order in the industrial towns troops had to be recalled in November from Portugal."

"Thus Bonaparte's threat to conquer the sea by the land was a very real one for the rulers of England in the closing months of 1800."

"On every horizon on which the Cabinet in London looked out that autumn of 1800, storms were rising. The Tsar's embargo, followed by his impetutous approach to Sweden, Denmark and Prussia to revive the Armed Neutrality of the North, threatened to both break the blockade of France and to close the Baltic to British trade. Already in November Prussia, angered by the seizure of one of her ships carrying contrabrand, had marched into Cuxhaven, a port of the free city of Hamburg and one of the chief channels of British commerce with central Europe. The First Consul's purpose was plain. It was to make the sea useless to the country which ruled it. "

Then early in December 1800 came the battle of Hohenlinden.

An overconfident Austrian army under the Archduke John stumbled into an expert defense by Moreau just outside of Munich. Materially, in terms of lost troops and cannon, it was a worse defeat of the Austrians than any of the many Bonaparte had managed to impose.

Moreau drove on towards Vienna.

On Christmas day the Austrians sued for peace. Britain was left facing France without any major allies.

Now in neither poker nor diplomacy do the players like to tip their cards, and in both activities the players often bluff, so it's not possible to be certain, but it appears that sometime in the last days of 1800 and the first month of 1801, that the leadership of Britain reached the conclusion that they must have peace if they could somehow manage to negotiate it.

Britain's situation was indeed dark.

Not only was she bereft of major allies on the continent, but the neutrals and smaller allies at continent's periphery, through which the trade her finances depended on passed, were becoming lost to her.

In northern Europe a League of Neutrality, actually hostile to Britain, was forming in the Baltic and on the North Sea threatening to deprive her of food for her poor and supplies for her navy.

In the south Portugal a vital ally both commericial and naval was being threatened, as was the Neapolitan Kingdom that ruled southern Italy and Sicily. Malta had been retaken but an attempt on Eygpt seemed likely to be costly but uncertain as to result.

Ireland as usual was restless. An effort to resolve the problem was made with the Act of Union enacted on 1st January 1801. Ireland's independant but Protestant only parliament was dissolved and Irish seats were created in the parliament in London.

Pitt had intended that this act should be accompanied by a Catholic Emancipation by which the Catholic Irish would be given a voice in London, but not control over Ireland.

King George, as the conventional story goes, was having none of this, being old and reactionary, and Pitt resigned over the issue on the 4th of February 1801.

Only it wasn't so simple and very convenient both.

Not so simple because it took a month and a half for Pitt's resignation to become effective. During which period he introduced a major budget with greater than ever funding for the war. When he did hand over power it was to member of his own party ableit one known to favor peace.

Convenient because by his resignation Pitt managed to signal the Irish Catholics that they could expect concessions once the old King was gone, and the French that the British were now open to making peace. He also managed to distance himself from responsibilty for that peace despite openly and fully supporting it. Very convenient.

And in fact, Addington, Pitt's peaceful protege made secret overtures to French for peace talks immediately upon assuming office in March 1801.

Events outran the ability of the leadership in Europe's capitals to act on them.

Just as the League of Armed Neutrality put together by Czar Paul began to act against Britain, and as Napoleon was putting his hopes of bringing Britain to her knees in an Alliance with the Czar, Paul was assasinated on the 23rd of March. His much more pro-British son Alexander succeeded. Napoleon when he heard of this was convinced it was British plot.

Already at the end of March and beginning of April before hearing of this Denmark took Hamburg, and Prussia Hanover, closing all the ports of northern Europe to Britain. Then came the news of the battle of Copenhagen on the 2nd of April 1801. Nelson had defeated the Danish navy and forced its capital to surrender.

It's main instigator gone and defeated almost before it started the League of Armed Neutrality had been neutralized at its very inception.

Denmark, Prussia, and Russia all lifted their embargoes during the late spring and summer of 1801. Napoleon's efforts to strangle British trade in the north had failed.

He had better success in the south. In May of 1801 he pressured Spain into the so-called "War of the Oranges" against Portugal.

Even here he did not obtain the full success he wanted. He did get the Spanish and the Portuguese to agree to close their ports to British ships. He also got an indemnity from the Portuguese.

He did not get to occupy and portion up Portugal as he had hoped. The Spanish weren't completely happy about being French catspaws.

In southern Italy he had somewhat better success.

The Neapolitans under the Austrian General Mack were defeated at Siena in Tuscany in January of 1801.

The peace imposed was not merciful. Among its strictures was the requirement that the ports of southern Italy be closed to the British. French garrisons were put in place to ensure it.

In the Mediterranean, at least, the war seemed to be going France's way.

Given this Bonaparte strung out the peace negotiations asking for additional concessions from the British at each stage.

To keep up the pressure on them he made elaborate public preparations for a cross channel invasion. The Royal Navy didn't think it was a serious threat but the British public and her politicians did.

Over the summer, however, it became obvious his plans to ally with Russia and strangle Britain's trade with the Baltic had failed.

On September 17th 1801 he received news that made it clear that Egypt was about to fall to the British. One of the major concessions he'd already made in the peace negotiations was to agree to evacuate Egypt. A concession about to be rendered worthless. It being obvious he already had reached the best terms he could hope for he ordered his negotiators to wrap up the peace talks before the 2nd October, that being the date the British leadership in London could be expected to receive the news of their success.

The British people hearing of the proposed peace on October 1st broke out into joyful celebration at the end of a decade of war. When the news came of British success in Egypt came on the morning of the second no one was in a mood to re-negotiate the peace.

It was something that certainly led to a bad taste in the mouths of many of the British elite. It was certainly nothing that led them to trust Napoleon Bonaparte more.

By being tricky and driving the hardest bargain possible Bonaparte had reduced the chances of a lasting peace. Worse he formed the opinion that the British leadership was weak and easily bullied. The manner in which he acted on this belief in the coming year made renewed war even more certain.

It was success as a general that made Napoleon Bonaparte famous, but it was the promise of peace that brought him to supreme power in France.

In 1800 France was a mess after almost a decade of war and revolution. Bonaparte's position was anything but secure.

The victory at Marengo, the one at Hohenlinden, and the peace treaties of Luneville and Amiens, with Austria and Britain respectively, went a long way to securing his popularity with the French people.

But popularity with its people did not necessarily translate to solid support among Frances elites, and it did not change the fact that many problems remained.

Bonaparte set about solving those problems, and securing his own place, with his customary energy and intelligence even before peace with Austria was signed early in 1801.

France did not need just peace after the year of Revolutionary strife and upheaval, it needed to repair splits in the body politic the Revolution had opened up and it needed to be organized in a stable predictable way. The French people wanted an end to internal strife and disorder as well as an end to external war.

The old France had been a feudal mish-mash of many different juresdictions and laws. The Revolution had swept much of the old order away without replacing it with anything.

Perhaps Napoleon's most famous acheivement in the civilian realm was the Code Napoleon, a new nation wide civil code of laws sufficently simple that all could understand it. A code in which all male adults at least were equal before the law.

He created a committee to work on this code in August of 1800. The new code was promulgated in 1804. It has not only remained the basis for the law in France ever since but outside of the Anglo-Saxon Common Law countries served most of the rest of world. Starting directly with the parts of Europe then under French control, the Netherlands, Switzerland and most of Northern Italy it was widely copied elsewhere.

Bonaparte appealed to the mass of the rural peasantry outside of Paris and the other cities by affirming they could keep the lands that the Revolution had confiscated from the nobility and the Church.

He appealed to the peasantry's traditional side by restoring the old calender with its many holidays (also appealing to urban workers) and by reaching a Concordat with the Catholic Church. Negotiations opened in the summer of 1800 after the victories at Marengo and Hochstadt and the Concordat was signed in July 1801.

The French state kept the land it'd taken from the Church, and Bonaparte got to appoint its bishops, but Catholism was once more accepted as the official religion in France.

In education the clerical primary schools were reopened and three hundred secondary schools opened across the country. Elite Lycees were also opened.

Also popular with the mass of people was the reduction of conscription.

Taxation was kept moderate, and when in 1802 grain prices threatened to get out of hand the government stepped in to control them.

Public works increased employment and drove business. New canals were built, roads were pushed over the Alps, and three great naval bases built at Cherbourg, Brest and Antwerp.

In Paris new bridges and the Arc de Triomphe were built. The Louvre was converted into an art gallery and museum.

The wealthy middle class was appeased by the placing of the nation on a more stable financial basis.

A national Bank of France was established in 1800. A forced loan may not have been popular and likely neither were the new corps of tax collecters but at least the money was solid again

Even the old nobility was placated. In April of 1802 many emigres were allowed to safely return to France.

Before renewed war with Britain made the effort moot Bonaparte also tried to revive French's former colonial empire. He sent an expedition to San Domingo (Haiti) in May 1802 to retake that island which had had exports exceeding those of all the United States in value not long before. He also reacquired Louisania from Spain and made renewed efforts to revive French prospects in both the Levant and India.

He started to re-build the French navy.

Everything Napoleon Bonaparte said has to be taken with a grain of salt. He said things to produce results he wanted often without regard to what was true or what he actually believed. Even so when he was recorded as saying in the future he might be better remembered for his civic accomplishments rather than his military ones he might have been serious. Particularily when in the next breath he admitted in the short term at least it was those military accomplishments that were his main claim to fame.

A fame that he depended on to remain in power.

In any event in just a few short years Napoleon was able to substantially re-order and strengthen France and bring it much more firmly under his own control. Probably much more so in 1804 or 1805 then in 1801 a point to remember when evaluating how much his foreign policy was dictated by playing to the gallery of French public opinion.

Given his need to appear militarily sucessful he may have had less leeway in compromising to achieve peace than it seems to us now. The temptation to reinforce his reputation internally by going to war might have more practical than megalomaniacal.

In sum he put considerable personal effort into strengthening France during the short period of peace granted him.

On the evidence it's not impossible that he was a basically practical man who would have welcomed a peace to establish his dynasty and fame with subsequent generations.

Ambitious true, but not necessarily fixed on world domination gained by the means of war.

Unfortunately competant as he was Napoleon was not a miracle worker.

As happy as the mass of the French people might have been over the end of war, and a newly prosperous and orderly country, the elites remained an untrustworthy group of trimmers.

The revolution had purged the French leadership of everyone with fixed principles or who was incapable of extreme flexiblity in the face of changing circumstances.

Those who were left were amoral, very flexible, ambitious and disloyal. They didn't see Napoleon as much more than a jumped up general and they didn't see by and large why they shouldn't put themselves in his place if they could.

Particularily as many of them were generals themselves. Napoleon had inherited the same problem that had plagued the Directory. He had a large army to pay for. He mainly managed to do so by milking foreign states. Bringing that army home and trying to disband it might prove very bad for his political health.

To do so in the face of foreign threats and plots all the more so.

This is the background against which Napoleon's bluster, untrustworthiness, and concern for military glory has to be judged. He couldn't be seen to be weak. Worse he worked under a constant pressure to exploit those who were weak in order to maintain the armies his regieme depended on.

In a way he'd trapped himself by obtaining such lop sided terms in the Treaty of Amiens.

A more sustainable peace would require concessions he was ill prepared to make.

In any case although there is evidence Napoleon believed the peace to be temporary and that he had reasons to not entirely regret that, the renewal of the war was not his doing.

Many histories in English pass over the fact that it was the British that renewed the war. When they don't they often moot the fact by asserting that Napoleon forced the British to fight by being so unreasonable.

Despite this it's clear that Napoleon was not prepared for the war when it came. He in fact appears to have hoped for at least another couple of years to rebuild his navy and France's colonies.

Take it as given. So the question is why did the British renew hostilities?

Part of it is simply that the conditions that led them to make peace were temporary and had passed.

In late 1800 and early 1801 there'd been two poor harvests and people were starving. Russia under Czar Paul was threatening an alliance that would cut off the British off both from grain to feed that hunger and strategically from the naval stores she needed to maintain her supremacy at sea.

By the second half of 1801 Czar Paul was dead and matters were looking a little better, but the British government under Addington had committed itself to peace. A peace desirable all the more for the fact that the war had brought nothing much more than colonies she didn't need.

By the time some military success had been achieved in Egypt the British government had already agreed to a preliminary treaty peace and couldn't back down in the face of public opinion.

A good harvest and peace put an end to the threat of hunger and an uprising of the poor. It also opened up the markets of Northern Europe to British trade again.

The Danes and Prussians pulled out of Hamburg and Hanover respectively. The new Czar, Alexander, seemed as friendly to Britain as France.

The agreements to return not just France's colonies to her, but also the Cape to the Netherlands (French puppets as the "Batavian Republic"), and to evacuate both Malta and Egypt seemed excessive in face of what the actual situation had been at the war's end.

Moreover the British people had had two expectations of the Treaty that had not been a formal part of it.

First, they'd thought peace would bring a renewal of trade with the continent. It didn't. The British lifted their embargo of France, France did not lift its embargo of British trade.

Second, the British hadn't been formal parties in the treaty of Luneville, but their King was also Elector of Hanover with a constitutional right to be consulted in any reorganization of Germany. It had been the British expectation (or at least hope) that Napoleon would abide by both the letter and spirit of that treaty and that this would mean a France securely contained within the new boundaries the Revolutionary Wars had given her. They had hoped for a stable Europe based on a balance of power and a modest degree of trust.

With the Prussians and Austrians both terrified of a renewal of war with France, the Russians basically disinterested, and Britain completely ineffectual on land there wasn't a much of a balance of power on the continent.

Worse rather than withdrawing her troops as agreed, and allowing a modicum of independance to her satellites as hoped, Napoleon seemed to determined to interfere with, and to nibble away at territory of, his weaker neighbours.

To quote one British historian: "The real cause of the war, as is now admitted on both sides, was Napoleon's shameless behaviour to the United Provinces in breach of the Treaty of Luneville. Before the ink was dry he had reduced Holland to the condition of a subject-ally of France. His similar behaviour in Northern Italy and Switzerland intensified the resentment his breach of faith aroused; but the virtual annexation of Holland was what a renewal of the war inevitable. It touched our traditional policy to the quick. The menace to our position in the Narrow Seas was one we had never been willing to endure."

Napoleon's retort to British protests was that Britain wasn't a signatory to the Peace of Luneville and it was none of her business. Technically true in a formal way, but practically nonsense and one suspects Napoleon must have known that.

Why exactly Napoleon felt he had to intervene in Switzerland, Holland, and Piedmont is unclear. The standard explanation in English that it was blind overbearing ambition seems lacking. Kagan suggests outright misunderstanding on both sides of the situation. To add anything to the conversation will take more time and research than I can hope to do for this post.

Whatever the case Napoleon's actions alarmed the British and the way in which he presented them convinced them that he couldn't be trusted. The British were convinced, or at least they claim to have been convinced, that the peace was just a pause in which Napoleon was making preparations for a renewal of war on more favorable terms for France.

Hence they decided they must renew it while the situation was still to their advantage.

In April of 1803 they replied to harsh harangues of their envoy in Paris during February and March of 1803 with a set of demands. These included the retention of Malta for ten years and its replacement as a naval base by a nearby island (Lampedusa) after that. France was also to evacuate Holland and Switzerland, and to indemify the King of Sandinia for the loss of Piedmont.

Unsurprisingly Napoleon rejected these terms.

On the 18th of May 1803 Britain renewed the war. She managed to catch the French navy dispersed and to drive it from the oceans.

Much of the following two years saw the British whale and the French elephant striving to come to grips with each other.

In the event Napoleon's efforts alienated the rest of Europe especially Russia and in 1805 Czar Alexander allied with the British and managed to bring Austria into that alliance in the Third Coalition.

And so the path to Austerlitz, Jena and Moscow was opened. The Napoleonic Wars proper began.

Kagan's book explores whether the war between Britain and France need necessarily to have led to war on the continent. Certainly neither Prussia nor Austria, who were necessarily going to be in the front lines of such a war, wanted it. Even Russia under Alexander didn't see such a war as unavoidable.

That the British and Russians saw Napoleon as untrustworthy with ambitions that threatened their interests is indisputable.

One senses, however, that they underestimated just how dangerous and costly war against him would prove to be. They did not yet appreciate either the strength of the refurbished French armies or Napoleon's own genius.

Perhaps if they had and Napoleon had done more to allay their fears of his ambition the world might have been spared the Napoleonic Wars.