Napoleon Bonaparte's Second Italian Campaign.

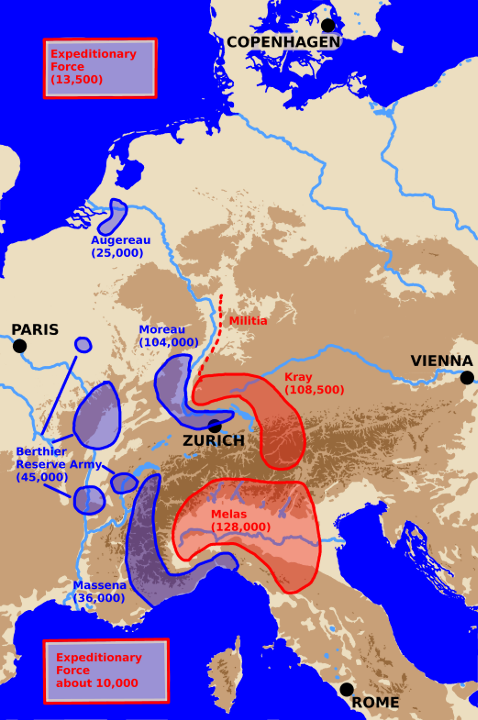

A map showing armies at the start of 1800.

The map above shows the location of the opposing armies at the beginning of 1800. It follows the West Point Atlas closely. The army numbers are from it. Arnold has somewhat different numbers. Arnold's numbers gives the French larger forces and the Austrians smaller ones. He gives Moreau 120,000 men vs 95,000 for Kray. He gives Melas only 100,000 men though Massena remains at 36,000. He has the Reserve Army under Berthier's nominal command with 60,000 men but "theoretical". He gives a Russian force of 25,000 in the Channel islands (this is what Napoleon imagined it might be) and no numbers for the English expeditionary forces available in the North Sea and Mediterranean. Given that the Allies had just evacutated a 40,000 man force from Holland (28,000 British and 12,000 Russian) and accounting for losses there may have been 15,000 British troops and 8,000 Russian ones available for amphibious operations in the North. Not far from what Napoleon feared.

The French situation at the beginning of 1800 was not as bad as it had in mid-1799 but it was still precarious as was Bonaparte's hold over France.

France's outnumbered armies were in poor shape. Conscription was proving difficult and those the government did manage to round up deserted in droves. Partly because of their poor supply situation. They were lacking food, footware, clothing, weapons and ammunition. The fighting generals blamed large scale theft by those appointed and paid to provide the supplies.

Even worse France's best supplied and most numerous army was that in Germany under the command of Moreau.

Southern Germany was the natural launching pad for an attack on Vienna. As Bonaparte needed a quick decisive victory to consolidate his rule an attack through Southern Germany along the Danube valley was his first choice of plans. Unfortunately Moreau was not inclined to co-operate. Neither quick, decisive operations nor co-operating with rival generals were part of Moreau's style.

As Chandler writes "Bonaparte was undoubtedly the master of the alternative plan."

Bonaparte scrapped together a new army in the area around Dijon. Poised to march to either Germany or Italy the new army was far enough from the frontiers of both as to not to seem an immediate threat. Even the new army's name "The Army of the Reserve" was intended to be misleading. Bonaparte employed multiple strategems to keep his new force from appearing the threat it was. When it moved he intended its attack to be a surprise.

The surprise Bonaparte decided on was an early crossing of the Alps to take Mela's army in Italy in the rear and cut its supply lines. Mela's army was facing Massena's in the Maritime Alps and along the Italian Riveria.

Bonaparte as Chandler alluded always had multiple plans ready for whatever his enemy did and to allow for the unexpected. He planned carefully but he was pragmatic about plans not working out. Just the same he had a favorite plan in mind. While Massena held Mela's attention on the Riveria incidently denying him supply from the ports there he would appear suddenly in the rear of the Austrians marching over the marginal but direct Great St. Bernard pass from the area of Lake Geneva. He would threaten to attack the Austrians in the rear by appearing about to march through or past Turin, but he in fact would march laterally screened by the Po to take Milan a city both politically and logistically important.

Small brigade to division sized forces would attack via the Mount Cenis, Little St.Bernard, and St.Gotthard passes both to ease the problems of sending his entire force via the Great St.Bernard and to confuse the enemy as to where his actual attack was occuring.

A major attack by General Lecourbe's veteran corps, 25,000 men strong, detached from Moreau's Army of Germany would be made south through the Spulgen pass securing a good supply line from Germany to Milan. Lecourbe's force would join Bonaparte's Army of the reserve in the vicinity of Milan.

Minus screening forces west along the northern bank of the Po and east towards Verona and Mantua the combined army would attack south and cross to the south side of the Po at or near Piacenza.

From the vicinity of Piacenza the massed French would turn west and secure the Stradella defile between the Po river and the Appenine mountains. There are only 12 miles (20 km) of flat land between the mountains and the river there and the plain was dominated by the stone buildings of the village of Stradella.

Holding Genoa, the north bank of the Po, and the Stradella defile the French would have cut the Austrians off from their supply lines to Austria. Bonaparte would have surprised Melas and trapped him in a pocket.

In Bonaparte's ideal world the surprised and panicking Austrians would be retreating in disorder and would encounter the massed French army in the excellent Stradella defensive position and be defeated piecemeal. In detail as the technical jargon has it.

It didn't happen exactly like that.

The Austrians attacked first. Melas split Massena's Army of Italy in half. Massena was locked in Genoa while Suchet retreated with the rest of the army down the Riveria past Nice. Bonaparte had to launch his campaign early. Moreover, though Massena managed to hold on long enough to keep Melas from blocking Bonaparte's exit from the Alpine passes he had to surrender Genoa in the end.

The march over the Alps also had its problems. Fort Bard blocked the main road until June 2nd holding up most of the Reserve Army's artillery and complicating its supply.

Finally the full corps of 25,000 veterans Moreau was suppossed to send over the Splugen was replaced with 11,500 men commanded by Moncey.

Despite this Bonaparte's manouverings up to June 9th followed the basic schema he'd forseen. He crossed the Alps before the Austrians could react and then marched east on Milan screened by the Po to the south, from Milan he turned south, crossed the Po and marched to take the Stradella defile.

Lannes secured that defile with the Battle of Montebello on June the 9th.

Because of Genoa having fallen. Bonaparte had to take the offensive at that point rather than standing on the defense. That almost didn't work out.

In the end though Bonaparte had the major victory at Marengo he needed.

That's it in broad strokes. Now for more detail.

The Austrians attacked in Italy on April the 5th. By the 19th Massena was beseiged in Genoa.

Reports of the Austrian offensive led Bonaparte to decide on the Great St.Bernard route on April 27th. Orders went out. The Army of the Reserve of some 60,000 men started to move.

On May 5th Bonaparte learned Massena was besieged in Genoa and only had provisions to last until May 20th. He sent orders to Berthier to "Force the March". Bonaparte himself slipped out of Paris early on the 6th. By the 9th he was in Geneva and had taken de facto command of the Army of the Reserve.

The Army started to cross the Great St.Bernard pass on May the 14th.

A map showing armies in Northern Italy on 14th May 1800.

The crossing of the Great St.Bernard by the Army of the Reserve makes a fascinating story. The pass was not really suitable for traversal by a large army that early in the year. It took some careful planning and unconventional thinking to pull it off. It was a dramatic operation. For the purposes of the overall narrative only two points are really important though.

One, the operation was effected quickly before the Austrians figured out was going on and with minimal loss.

Two, Fort Bard turned out to block the main route preventing the easy passage of supply wagons or guns and it held out until June 2nd.

The Army of the Reserve made into the plains of Northern Italy but minus most its guns and supply train.

To some extent it made these lacks up via plunder and the capture of Austrian guns and supplies. Still the French felt the lack of cannon, supply wagons, and ambulances as late as the Battle of Marengo on June 14th.

That's getting ahead of our story. By May 24th the bulk of Army of the Reserve had essentially completed its crossing. The infantry, cavalry, and a few guns were across.

Lannes and Duhesme's corps were in the lead around Ivrea where the plains began, Victor and Murat were in the valley behind them but over the pass. As was Bonaparte himself at Aosta.

Lannes faced an Austrian force under Haddick. Lannes would secure the staging area for the Army of Reserve around Ivrea with the Battle of Romano-Chiusella on May the 26th.

Neither Bonaparte nor Melas had a clear picture of what was happening overall at this time. Melas knew French forces were pushing through the Alps by this point but he didn't know by which route the main French forces were coming and he significantly underestimated the size of the threat. Just the same he'd started moving reinforcements to deal with the threat. He was himself marching north with 9,000 men detached from the Army on the Riveria. He left Elsnitz with about 18,000 men to deal with Suchet near Nice and Ott with 21,000 to keep Massena confined to Genoa.

Turreau with a brigade was pushing over the Mount Cenis pass. Neither Army commander was clear about what was happening with him. As happened he was repulsed by the Austrians at Avigliano on the 24th of May. Still he'd succeeded in his main mission of confusing the Austrian command.

A map showing armies in Northern Italy on 24th May 1800.

Having crossed the Alps and having most of his Army concentrated around Ivrea it might have made sense for Bonaparte to attack south. He could expect to catch Melas main forces but piecemeal while still forming up and with the element of surprise. It was the most direct route to relieving the desperate Army of Italy under Massena still holding out in Genoa.

Instead Bonaparte decided to stick to his original plan of cutting off the Austrian Army's supply lines. Throwing out a screening force under Chabran along the line of the Po he moved with the bulk of his forces east to Milan.

Not only was Milan importantly politically and logistically but this move would allow him establish new easier to traverse, and more secure lines of communication over the Simpleon, St.Gothard, and Splugen passes.

On May the 27th Moncey with two divisions from the Army of Germany (11,500 men) crossed the St.Gothard and drove the Austrians out of Bellinzona.

On May the 29th Bethencourt having crossed the Simplon with a single small division drove the Austrians out of Demodosolla.

On May the 31st the main army under Bonaparte crossed the Ticino river on their way to Milan. On the same day Melas ordered his forces to concentrate at Alessandria the critical fortress that Marengo lies just to the east of.

Elsnitz moved with his entire force but lost half of it in the barren mountains due to poor supply and being constantly dogged and harassed by the pursuing Suchet. Ott in violation of the strict letter of his original orders hung on around Genoa to patch up a quick surrender on favorable terms by Massena. Ott split his forces leaving part to garrison Genoa, sending part to Alessandria, and a brigade each to Tortona and Piacenza.

On June the 2nd Bonaparte entered Milan.

At this point each side was running three different races. They were trying to secure the critical fortified points in Northern Italy and indirectly the Austrian communications. They were trying to effect full concentrations of their field forces, and they were racing to control the key defile at Stradella where the Appenine mountains make their closest approach to the Po river and the flat fertile lands around it.

It should be noted here that the main issue with mountainous terrain was not its being physically impassable. Infantry, and even cavalry could manage to find a way forward through almost any terrain. Artillery and supply waggons had more trouble but Bonaparte showed this didn't have to be a showstopper. The main problem with mountainous terrain was its low population and poverty. Armies still mainly sustained themselves by "foraging" on the local population. Low population, or a poor population, or one that had already been looted clean meant your army would starve.

This is what happened to the force under Elsnitz of almost 20,000 men. Forced to withdraw over poor terrain that had already been stripped of what supplies had been available the Austrian force lost over half its strength without being in a major fight.

Without good lines of communication this was the fate any force of the time faced and the commanders of the time all realized it and took account of the fact.

A map showing armies in Northern Italy on the 5th of June 1800.

Bonaparte arrived in Milan on June 2nd. It tood him several days to fully assemble his army in the area. Some commentators believe he lingered too long in the city dealing with political and other secondary matters. This seems unfair. Men are not machines, neither Bonaparte himself or the troops under him.

Lannes reached Pavia on June 2nd. Duhesme reached Cremona on the 4th of June. Massena surrendered Genoa on the same day. On the 5th Moncey's corps joined Bonaparte in Milan.

Bonaparte's next move was to move south cross the Po near Piacenza and move west to secure the Stradella defile.

Boudet's division and a cavalry force under Murat severely diminished by a variety of detachments reached the Po bridgehead near Piacenza on the 5th but despite the weakness of the Austrian forces there were unable to take that day.

An additional brigade of Austrians under O'Reilly reached Piacenza on June 6th.

Lannes, Boudet, and Murat all managed crossings of the swollen Po on the 7th. O'Reilly managed to withdraw across their front to Stradella. The outnumbered O'Reilly was forced out of his position on the night of the 7th and the 8th. Really very early on the 8th. Melas and Ott were rushing reinforcements to him.

The 9th of June say a kind of meeting engagement just to the west of Stradella. Called the Battle of Montebello this saw Lannes defeat Ott despite inferiority in guns and total numbers of men. Lannes began (somewhere between 5,000 and 8,000 men) with a slight numerical advantage over the Austrian rearguard under O,Reilly (3,000 to 4,000), then at a distinct numerical disadvantage against Ott (17,000 men in total), then finally only a slight disadvantage when Victor (6,000 to 8,000 men) came up with reinforcements.

Supposedly Lannes only had 4 guns against 35 of Ott's but eyewitness accounts make it clear Lannes had managed to loot more guns during his march and that Victor also brought additional guns to the battle. The Austrians appear to have over relied on their superior strength in guns and to have used them inefficently. A story that was to be repeated at Marengo in three days.

A map showing armies in Northern Italy on the 12th of June 1800.

By the 13th of June Bonaparte had managed to concentrate most of his army on the plain to the west of the Austrian fortress town of Alessandria. The village of Marengo was part of his front line. Melas had managed an even greater concentration of his forces in Alessandria but Bonaparte was unaware of this.

Bonaparte thought the Austrians were trying to escape but he wasn't sure by what route. He dispersed forces to find them and to cut off possible routes they might be using. He sent Desaix south with Boudet's division. He sent Lapoype's division north towards the Po.

Actually Melas had concentrated superior numbers. He had between 31,000 and 40,000 men in or around Alessandria. He enjoyed even greater superiority in artillery and cavalry.

The Austrians did have a problem in that they had only a single narrow bridgehead over the Bromida to bring those superior to bear. For some reason they not only failed to improve the capacity of that egress they actually took down a pontoon bridge they'd previously had downstream of it. Unfortunately this sort of shoddy staff work was typical of the Austrians at the time. Since efficient staff work was something new at the time perhaps it'd be fairer to say they hadn't yet caught up with the new standard the French were setting.

In any event the Austrian brigades only shuffled across the river and out on to the plains to attack slowly and one at a time on the morning of June 14th. The day of the soon to be famous Battle of Marengo.

It was a battle the French were almost to lose twice.

The initial Austrian blows fell on troops commanded by Victor. He commanded the divisions of Gardanne and Chambarlhac in front of and around Marengo. The fighting began around 0700 am. The first serious assault came around 0900 am. FML Haddick pressed the attack and by 1000 am the French still fighting hard began to withdraw. They reformed on Marengo. Haddick was mortally wounded and Bellegarde took his place but Haddick's division was fought out.

A fresh Austrian division under Kaim took up the attack. The French were reinforced by Lannes who formed on Victor's north flank. Vicious back and forth fighting took place in the village of Marengo itself.

"Around 11 a.m. a lull descended on the field while the Austrians rearranged their batteries and brought up fresh troops."

The battle resumed around noon with Austrian threats to both the French flanks.

To the south a cavalry brigade under GM Pilati attacked. An outnumbered French cavalry force by the junior Kellerman counter-attacked. With perfect timing he broke the Austrian force. Arnold writes " Pilati's men never recovered from the shock and confusion of this encounter."

"Around the time Pilati's troopers engaged, FML Ott (6,862 infantry; 740 cavalry) finally managed to shake free of the snarl at the bridgehead and march against Castel Ceriolo."

The French nothern flank was threatened. Arnold continues: "Until now, the French had been able to contend with their foes along a limited front where they could match the enemy strength. It had been a battle of attrition, but one that the French could endure because of the defensive advantages of their position. Ott's maneuver threatened to upset the equilibrium. Lannes hurled Champeaux's cavalry brigades against Ott in a desperate effort to contain his breakout. The two understrength regiments charged gallently. Champeaux fell at their head with a mortal wound. In spite of their efforts they made little impression against the Austrian infantry squares."

"After repulsing the French cavalry, Ott's infantry occupied the hamlet of Castel Ceriolo and the adjacent high ground."

"At about 12:45, Ott faced his infantry south and marched them toward Lanne's flank."

Lannes refaced some of his troops and committed his reserve. It wasn't enough. "By 1 p.m. Victor and Lannes had committed all their troops to hold their line."

In Marengo "[b]y 2 p.m., the combination of continual frontal pressure and Ott's advance rendered the position untenable."

Victor and Lannes ordered a retreat.

The Austrians thought the battle won. Arnold writes "A complacent overconfidence took hold."

Just how badly the French retreat went for them remains a question of controversy. Some men fled and debris littered the field it seems agreed, that other men remained with their colors and continued to fight hard is also agreed.

At this point both Bonaparte with his guard and a fresh division under Monnier appeared. They heartened the French surviors and bought time. They didn't stop the Austrian advance permenantly. Just the same the retreating French although battered were not yet completely broken.

It was 1500 hrs, 3 p.m., Melas the Austrian commanding general, injured from having two horses shot out from underneath him and tired, decided the battle was won and left the field. This didn't help the morale of the Austrian troops.

Desaix arriving with Boudet's division also thought the French had lost the battle. He told Bonaparte so, but Desaix thought there was time to win a new battle.

Reinforced with Desaix's fresh troops the French counter-attacked the shocked Austrians at around five. Perfectly timed and co-ordinated artillery, cavalry, and infantry attacks shattered the head of the pursuing Austrian column under St. Julian.

The Austrians broke and spread their panic to their rear.

Having fought hard all day and believing themselves victorious only to face a vicious unexpected French counter-attack the Austrian army routed.

A single grenadier brigade under GM Weidenfeld stood and prevented the capture of the routing central Austrian column.

By nightfall the Austrian rout had reached the village of Marengo.

The battle was over in reality now, and it was a French not an Austrian victory.

Bonaparte had cut off and defeated the Austrian Army of Italy but he hadn't yet actually destroyed it.

He needed to get back to Paris.

The next day "[f]earful of what might happen if hostilities resumed, at 10 p.m. Melas signed the Convention of Alessandria. Its terms allowe the Austrian army to march intact eastward beyond the Mincio River. In return, Melas ceded all remaining Habsburg holdings in Piedmont and Lombardy. The Mincio was to serve as the boundary between France and Austria."

By June 17th Bonaparte was back in Milan. By July 2nd he was back in Paris. He was as much a politician as a general now.

The Second Italian Campaign and Marengo had not proved the knock out blow he'd hoped for.

Politically they were good enough to secure his position though.

Peace negotiations with Austria broke down the following November. A victory by Moreau at Hohenlinden brought the Austrians back to the table.

It wasn't ideal from Bonaparte's point of view, but with peace he was able to consolidate his position and restore a France exhausted by a decade of Revolution and War.

Note: You will need to cut and paste addresses given into your browser's address line in order to follow them.