Base Map

15th November

16th November

17th November

Bonaparte fights to maintain the blockade of Mantua once again. It was his closest call.

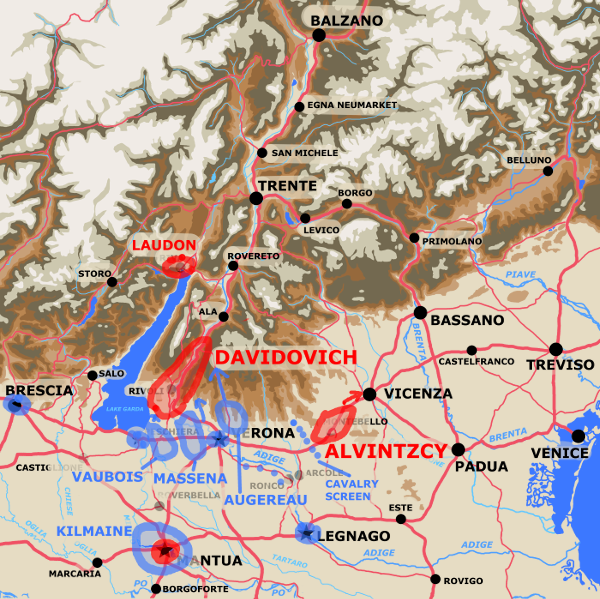

Map of the theatre of operations in Italy from October 31st to November 23rd 1796.

Map Key:

|

|

On the 24th of September FZM Joseph Alvintzy was appointed to overall command of the Austrian forces in the Italian theatre and given orders to relieve Mantua as soon as possible.

Within days Alvintzy was at Balzano making plans for a new offensive. Another pincer movement was decided upon. Davidovitch would attack down the Adige valley via Trente, Ala and Rivoli to Verona. Alvintzy, with twin columns under Quosdanovitch and Provera would attack from the Fruili east of the Piave river via Bassano and Cittedella, concentrate near Vicenza and march on Verona from there.

Despite desperate pleas for relief from Wurmser in Mantua it took time to rebuild the Austrian armies in Italy for the third time. It wasn't until the end of October that the necessary troops were assembled.

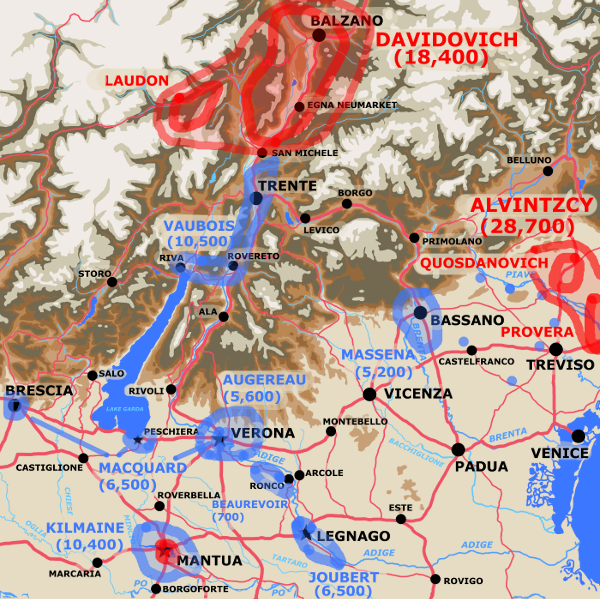

A Map showing Army Locations at the End of October.

The French were at their lowest ebb in this period. Twelve battalions of reinforcements from the Vendee, "The Army of the Ocean" in western France, were not enough to replace all the troops that had been killed, wounded or were now sick. The gaps weren't just in the ranks. Many of the those that had led the Army of Italy to its earlier victory were not now available, as Bonaparte complained bitterly and eloquently to his political masters.

On October the 1st Bonaparte summarized his position as follows:

There were 4,000 men in fortresses in Lombardy, 14,000 sick and 4,000 wounded.

Kilmaine commanded Sahuguet and Dallemagne in the blockade of Mantua.

Bonaparte had barely 19,000 men he could maneuver with and those split in two. Almost two thirds of his forces nominally 50,000 in strength were either incapacitated or tied up in static positions.

According to Martin Boycott-Brown by the end of October the situation was as follows:

For a total strength of 41,560.

Martin Boycott-Brown's source for this according to his footnotes was J.B. Schels, an Austrian who likely leaned heavily on Austrian sources so the numbers may be on the higher side, note nothing is said of sick or wounded.

The West Point Atlas (Map 20) shows a slightly different picture:

Which totals up to roughly 45,000 men, of which 28,000 were in the Corps of Observation available for field operations and another 17,000 that were either blockading Mantua or guarding vital points.

As usual when short handed Bonaparte was micro-managing the deployment of individual demi-brigades at this time. A full picture would require a deeper dive into the archival material than I've attempted. Nevertheless we know something of the subordinate units to the commands mentioned above. Kilmaine would have still had the divisions of Sahuguet and Dallemagne under his control each of about 4,500 men. Chabot may have been standing in for Sahuguet. We know Fiorella, Guieu and Gardanne were apparently commanding brigades under Vaubois. Joubert was with his brigade at Legnago persumably under Augereau's direction.

Alvintzy was overall commander of the Austrian forces in Italy. These forces were divided into two major corps, Davidovitch's in the Tyrol and Quosdanovitch's in Fruili. Davidovitch was based in Balzano and Quosdanovitch in Gorizia. After consulting with Davidovitch early in October Alvintzy went to Fruili which he reached by mid-month and essentially took direct command of the Fruili Corps.

As of about October the 21st Martin Boycott-Brown reports the Order of Battle of the Fruili Corps as follows:

Divided up into 24 2/6 battalions and 11 and a half squadrons this came to 26,432 men. Almost 15,000 of whom were newly raised, poorly trained, and under officered.

Note this amounts to six brigades commanded by Hohenzollern, Roselmini, Lipthay, Schubirz, Brabeck and Pittoni, each brigade with 4 battalions and a squadron of cavalry except for Hohenzollern who being the Advance Guard got 7 squadrons of cavalry. Sometime in the next week an additional brigade from the Tyrol under Mittrovsky joined the Fruili Corps making seven brigades and roughly 28,700 men available for Alvintzy's push on Verona.

The push on Bassano saw Alvintzy divide his forces into two columns the northern commanded by Quosdanovich with Hohenzollern as his advance guard. Quosdanovich also had Mittrovsky's brigade transfered to his command. Additionally by a process of elimination Quosdanovich had Roselmini's and Pittoni's brigades. Alvintzcy's southern column under Provera having Lipthay's brigade as its advance guard with in addition, according to Cuccia, Brabeck's and Schubirz's brigades.

The coming weeks saw Hohenzollern and Mittrovsky, as well as Provera and Quosdanovich, being given command of additional troops at times and acting as de facto division commanders under Alvintczy's overall command.

The usual warning about anachronistically projecting current notions of fixed and formally supported unit organization applys here.

Martin Boycott-Brown has Davidovich's Tyrolian Corps divided into six columns on November the 1st as follows:

For a total of 18,427 infantry and 1,049 cavalry in 15 battalions, 25 companies, and 10 squadrons

Note that the anomaly of Vukassovitch commanding two columns apparently came from Boycott-Brown's source which was J.B.Schels.

The 24,000 odd men in Mantua of whom maybe some 14,000 were effective should not be entirely forgotten as they necessarily tied down part of Bonaparte's forces.

The upshot of all this was that the Austrians had about 48,000 men in their two Corps of Tyrol and Fruili and another 10,000 at least potentially available in Mantua.

Bonaparte had only about 31,000 men (if you assume some of Macquard's men were reserves and others garrisons) immediately available for field operations and another 10,000 roughly around Mantua some portion of which he could free up in an emergency. In raw numbers the French were at a disadvantage.

This was offset by the facts that Bonaparte had the central position and was generally able to effectively co-ordinate all his forces, and that individually he matched or outnumbered each of Wurmser, Davidovich and Alvintczy.

A key point was that Davidovitch significantly outnumbered Vaubois and that the French were not aware of this. On the flip side once concentrated the French field forces significantly outnumbered Davidovitch alone and if Alvintczy did not keep Bonaparte occupied he could turn on Davidovich and beat him.

Of course if Davidovitch and Alvitnczy had joined they'd have outnumbered Bonaparte significantly. They did not in the event do this. Why is unclear. A concern to cover their both their bases in the Tyrol and the Fruili, issues with logistics maybe, or perhaps just a bad plan based on outdated precepts imposed by the War Council in Vienna it is not clear.

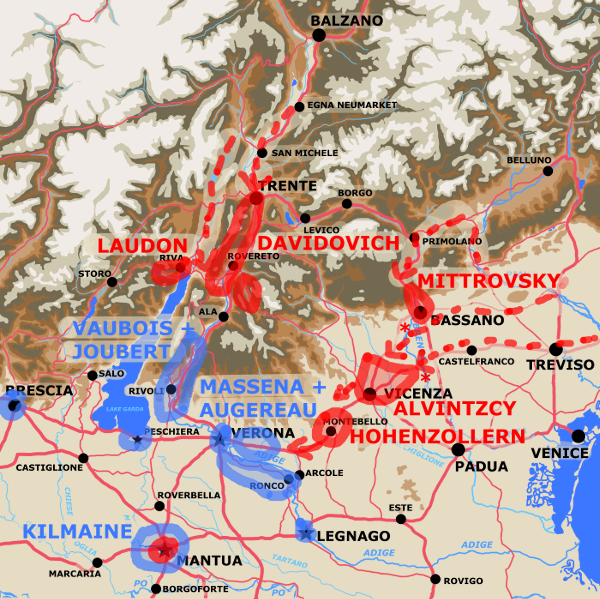

Map showing situation up to November 9th 1796

The French were completely unaware that Davidovitch in the north with the Austrian Tyrolean Corps had managed to obtain a significant numerical advantage over Vaubois division opposed to him. French reverses in Germany had freed up two brigades that had been holding defensive positions in that direction, but Bonaparte thought more troops had been shifted to the Fruili Corps.

For that reason Bonaparte ordered Vaubois to attack Davidovitch and once he'd fully secured his position to send reinforcements to Bonaparte's main part of the army in the plains to the south.

Davidovitch's intial attacks came first, the 27th, 29th and 30th of October all saw attacks despite heavy snow in the mountains.

Vaubois attacked early on the morning of November 2nd. The fighting was vicious and costly to both sides.

On November 4th Davidovitch advanced threatening to outflank Vaubois who fell back to Calliano. Davidovitch had reached Trent by November 5th.

By this time Bonaparte had become sufficently alarmed to order Joubert's brigade in Legnago to move to Vaubois's assistance.

At first Vaubois managed to hold at Calliano inflicting severe casulties on Davidovich's Austrians.

However, under threat of being outflanked, Vaubois sent off troops to Mori and Rovereto and Davidovitch attacking on November the 7th, after a back and forth battle, routed the French. We have first hand accounts of individuals fleeing the entire distance to the area of Rivoli some 22 miles or almost 40 kilometers to the south.

It took the French the whole of November the 8th to reconstitute their units. The Austrians having also lost heavily in the battles around Calliano failed to pursue vigorously.

Bonaparte was not happy and made this known to the units involved in no uncertain terms.

Very unfortunately for the Austrians Davidovich on November 9th hearing a rumor that Massena had been moved to defend Rivoli delayed his own march on that place.

Slow uncertain communications between the two Austrian Corps and the consequent problems co-ordinating their attacks plagued them constantly. As will be apparent from the account of the Fruili Corp's efforts below this proved very detrimental to the Austrian hopes of success.

Alvintczy with the Fruili Corps had set off before Davidovich on October 22nd. He was starting from Gorizia and had a considerable ways to go and at least two major rivers to cross before he could expect to engage the first major French forces under Massena. The march began with good weather but soon torrential rains were falling.

By October the 25th he'd reached the now swollen Tagliamento which had become too wide for his bridging train. Nevertheless the Austrian troops were able to ford it. At what cost to the troop's health and what delay to the army's trains is uncertain.

Martin Boycott-Brown writes that "it was only on the 28th that the concentration of the Fruili Corps became complete, when Provera moved to join Quosdanovich within reach of the Piave. Here the Austrians paused because it was impossible to throw a bridge over the river, which was still greatly swollen by the rains. The state of the rain-soaked roads, the rivers in spate and the stormy Adriatic Sea were also causing problems of supply for the Fruili Corps, much as Bonaparte had expected ".

On the night of October 30th the rain stopped and the rivers began to fall. On November 1st the Austrians bridged the Piave near Campana and their advance guard crossed.

Alvintczy himself crossed the Piave near Conegliano on November 2nd.

Massena who'd been concentrated around Bassano evacuated that town on November the 4th. Hohenzollern commanding the advance guard of Alvintczy's northern column under Quosdanovich entered Bassano on the same day. To the south Lipthay commanding the advance guard of Alvintczy's southern column under Provera entered Fontaniva on the Brenta.

The 5th of November saw the Austrians remain on the line of the Brenta. There was some fighting at Fontaniva but none at Bassano.

On the 6th of November the Austrian march resumed. Hohenzollern's advance guard leading Quosdanovich's column crossed the Brenta at Bassano. The French were advancing too. Massena moved on Fontaniva and during a hard battle that lasted all day inflicted severe losses on Lipthay's brigade. Reinforced later in the afternoon Lipthay held on. In the meantime Augereau had advanced against Quosdanovitch's column coming from Bassano. Again the battle lasted all day and the Austrians took severe losses but held their ground.

During the night of the 6th and 7th of November Bonaparte realizing that Vaubois was crumbling in the face of Davidovich's superior forces ordered Massena and Augereau to retreat. The Austrians under Alvintzcy woke on the morning of the 7th to find the French gone.

"In the morning of the 8th, Augereau, Massena, and the reserve arrived in Verona." Alvintzcy's Fruili Corps reached Vicenza the same day.

Alvintzcy's Austrians appear to have spent the 9th slowly following up Massena and Augereau without actually regaining contact. Their lead elements had only reached Villanova by the 10th. Alvintzcy apparently spent the day ineffectively trying to co-ordinate with Davidovich.

Map showing situation around Caldiero November 12th.

A Terrain Note: The map does not capture this well, it's lowest contour line being about 250 meters, but the mountainous terrain to the north extends down to the main Vicenza to Verona road. In fact at points across it; the main road crosses a ridge at Caldiero. This makes Caldiero one of the main strategic chokepoints in Northern Italy, lying on a ridge with mountains to the north and swamps to the south. This fact being reflected in the multiple battles fought at this location.

The 10th of November passed quietly. Davidovitch spread his forces out into a cordon defense. The bulk of Alvintzcy's continued to move from Bassano to Villanova. Mittrovsky's brigade held Bassano.

The 11th of November saw Alvintzy's advance guard under Hohenzollern performing a reconnaisance in force almost up to Verona. A counter attack by Augereau and Massena who'd been camped on the other side of Verona pushed Hohenzollern back.

The 12th of November saw the battle of Caldiero as Augereau and Massena made an all out assault on Hohenzollern's isolated brigade. Exact numbers are not available but initially Hohenzollern was heavily outnumbered, likely by two or three to one. Giving Augereau and Massena's divisions 6,000 men each and Hohenzollern 5,000, say twelve thousand to five thousand.

Hohenzollern was attacked to the front by Augereau and while Massena attempted to outflank him to the north. He was pushed back to Caldiero. The French had already been having problems due to heavy winter rains that not only impeded their movement but also wet their muskets rendering them unable to fire. At Caldiero they met well served Austrian artillery which gave them further pause. Austrian reinforcements began to arrive in the late afternoon, first Brabeck, then Schubirz, and finally Provera according to Boycott-Brown.

Brabeck and Schubirz presumably with the brigades they'd been commanding earlier in the campaign. Provera probably with a third brigade likely Lipthay's. The West Point Atlas has 6,000 Austrians spread out between Villanova and Bassano at this point in time. Seems probable these were the brigades of Roselmini and Pittoni. We know Mittrovsky and his brigade were back in Bassano.

If all the above supposition is correct by the end of the day the Austrians had four brigades facing the two French divisions at Caldiero. Giving each Austrian brigade 4,500 men and the French divisions 6,000 men each, this would be 18,000 Austrians to 12,000 Frenchmen, with the Austrians on the defensive with good artillery support.

The Austrian's lost about 1,200 men, the French according to some sources about 2,000.

The French under Bonaparte retreated to Verona. Bonaparte had been defeated in a stand up fight with his main army. French morale was depressed. Their situation was dire.

See the battles page entry for Caldiero for more details.

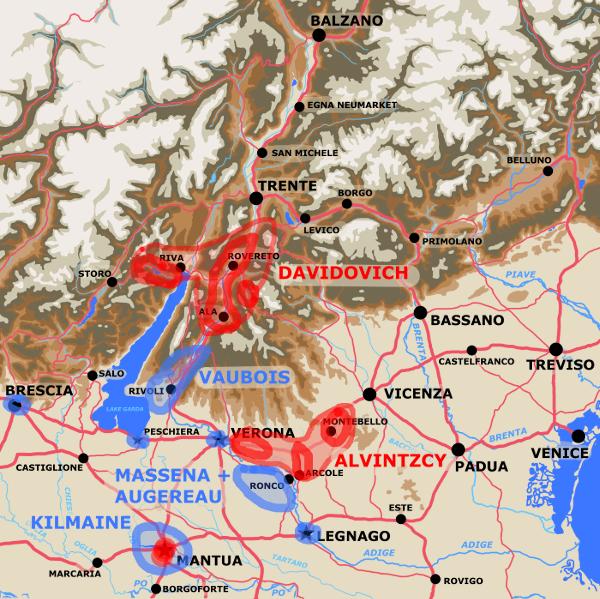

Map showing situation up to November 15th 1796

The French position after Caldiero was desperate, if Alvintczy managed to join either Davidovich or Wurmser Bonaparte's field army would be decisively outnumbered. In that case he could not expect to keep all three Austrian forces from linking up making the Austrian numerical advantage insurmountable and losing the key fortresses of Mantua and Verona in the bargain. The entire French position in Italy would unravel and Bonaparte would be lucky to save anything of his army

It has long been something of a mystery why exactly at this junction Alvintzcy and Davidovich didn't push their advantage more aggressively. Many campaign descriptions simply blame Alvintczy's and Davidovich's personalities basically in so many words calling them timid old men. Too cautious and too slow.

In addition to discounting questions of logistics and the fog of war this seems unfair on other grounds. Not just ones of Austrian 18th century military doctrine either. Nor just the fact that they were being compelled to follow a plan dictated to them afar by the war council in Vienna.

Phillip Cuccia writes in his book covering the seiges of Mantua that Alvintczy had explicit orders at this time to remain on the defensive as secret peace negotiations were about to begin. Bonaparte was an ambitious revolutionary general who'd accumulated some political capital, he was willing and able to defy his political masters at times. This was not true of the Austrian generals.

In any event not only did this give Bonaparte some breathing room, it likely constrained any response Alvintzcy could make to events. The hands of the Austrian command had been tied by their political masters. At this remove without being able to read the minds of the Austrian commanders it's likely not possible to be exactly sure of what effect this all had on events but it certainly wasn't a positive one from the Austrian point of view.

Bonaparte unable to procure victory by head on battle in the open field proceded, with political and psychological means, as well as via material attrition. Remember over half of Alvintzcy's troops were new recruits, raw, poorly equipped with too few officers. It is likely the severe losses the French continued to impose on the Austrians had a disproportionate effect because of being inflicted mainly on his good veteran troops.

Maps showing the area between Verona and Arcole on the days of November 15th, 16th, and 17th.

| Base Map

|

15th November

|

|

16th November

|

17th November

|

As he needed to defeat Alvintzcy and the direct approach had failed Bonaparte gathered his forces and made an indirect attack.

On the night of the 14th and 15th of November he marched from Verona with the full divisions of Augereau and Massena along the south bank of the Adige to the town of Ronco where he bridged the river.

This put him in the rear of Alvintzcy's army then threatening Verona. He was just south of Villanova where the post road from Verona to Vicenza bridged the river Alpone. If the French were to gain the road near Villanova Alvintzcy's army would be cut off.

Despite the threat that this represented to the Austrians the French themselves were in a delicate position. If they did not maintain a constant crediable threat to the rear of the Austrian army before Verona there was a chance the Austrians might successfully assault the city. Moreover the terrain between Ronco and Villanova in the triangle of land between the Adige and the Alpone was swampy and only passable via narrow easily defensible causeways.

The path to Villanova ran along one of these causeways to a bridge across the Alpone to Acrole and then north along the less marshy eastern side of the Alpone.

The path to Caldiero from Ronco, into the rear of the Austrians before Verona, also followed a causeway across the swamp to a village called Belfiore di Porcile.

Martin Boycott-Brown writes that the accounts of the battles fought in this area over the next three days are inconsistent. A plausible outline of events follows.

Augereau's division was directed on Arcole. Massena's on Belfiore di Porcile. This much seems agreed on, and it's plausible to believe Augereau was to threaten to cut the post road at Villanova while Massena was to threaten the rear of the Austrians in front of Verona.

The Austrians first heard of the French maneuver around 9:00 am on the 15th. Though first they believed it a fient they soon changed their minds and Alvintzcy reacted. He ordered his artillery and supply trains back from Villanova to Montebello. He ordered a brigade under a Lieutenant Colonel Gavasini to Belfiore di Porcil at 11:00am and Brabeck there at noon. It's unclear how many battalions or men Lt.Col. Gavasini commanded, but Brabeck plausibly commanded his usual troops of four battalions with three to four thousand men. In any event it was enough to bring Massena to halt around Bionde half way between Belfiore and Ronco.

Augereau in the meantime had been bogged down before Arcole where the last few hundred yards of the causeway leading to the bridge were completely exposed to fire coming from Arcole and the opposite bank of the Alpone. Worse around midday the detachment of Austrian troops there were reinforced by Mittrovsky's brigade which Alvintczy had ordered there from around Montebello.

The struggle in front of Arcole continued desperately for the afternnon and on into the evening. It was not successful but a flanking movement by Guieu's brigade which had crossed at Albaredo further down the Adige and moved up the eastern side of the Adige and Alpone did suceed.

Massena in the meantime after a hard confusing battle had managed to take Belfiore.

So by the evening of the 15th the French had taken both their objectives of Belfiore di Procile and Arcole at some considerable cost.

Bonaparte ordered a withdrawal that night. A controversial move for which the reasons are not entirely clear.

Bonaparte himself later indicated that he did not feel his position vis Alvintczy was sufficiently strong, and that he feared not being able to reinforce Vaubois quickly enough if Davidovich should attack.

Alvintzcy ordered a counter attack for daybreak on the 16th. Provera was to attack through Belfiore di Porcile with six battalions and two squadrons. Mittrovsky was to attack through Arcole with fourteen battalions and two squadrons. The two columns were to meet at Ronco. At that point Alvintczy would cross the Adige at Zevio halfway between Verona and Ronco.

These attacks ended disasterously for the Austrians. They were first stopped and then routed in disorder and with heavy loss.

Massena retook Belfiore but Augereau stalled before Arcole again despite Lodi like antics on the behalf of Bonaparte and others.

During the night of the 16th and the 17th Bonaparte made arrangements for Augereau's division to cross to the other western side of the Alphone and Adige by various means. Massena was to take over responsiblity for attacking Arcole across the causeways and via the bridge. General Robert being delegated the local responsibility as Massena also retained the position at Belfiore.

Alvintzcy in the meantime ordered Hohenzollern back to Caldiero from his position in front of Verona.

On the 17th Massena managed to administer a drubbing both to Provera once more, but also to Mittrovsky who had attempted another counter attack from Arcole.

That same day Augereau aided by a detachment from Legnago and Bonaparte's guides, fought his way bitterly up the west side of the Alpone, eventually taking Arcole. Mittrovsky managed to keep the post road open for the escape of Provara's troops. Hohenzollern had been pulled back earlier in the day. Alvintzcy's Austrians were in full retreat.

It was back at Montebello, at 3:00am the morning of the 18th, that Alvintzcy learned Davidovich had finally attacked Vaubois. Rather too late to decide the battle of Arcole.

See the battles page entry for Arcole for more details.

Map showing situation on November 18th 1796 and afterwards.

Davidovich attacked Vaubois on the 17th. Vaubois was vastly inferior in strength and had had to defend the Adige north of Verona against possible attack by Alvintczy too.

Technically given the balance of the forces present on the map the campaign was far from over. With generals bolder and quicker than the Austrians or against a French general other than Bonaparte that might have been true in fact.

Bonaparte knowing Vaubois had been badly defeated and was in full retreat wasted no time shifting his main force towards Davidovich leaving just his cavalry to follow up Alvintzcy's retreat.

Before daybreak on the 18th Massena's and Augureau's divisions moved off. Massena went via Ronco to Villafranca. Augereau moved north of Verona via the Val Patena to threaten the Austrian communications at Dolce and Peri as he had earlier in the year.

The co-ordination of the Austrian generals might be considered comic if the lives of men and the fate of Europe hadn't been in the balance. They were like dancers out of step. Messages between Davidovich and Alvintzcy were taking between one and three days to arrive. They attempted to co-ordinate their attacks in order to aid each other but happened in actuality was that when one advanced the other retreated, always allowing the centrally located more nimble Bonaparte to meet the more immediate threat with the better part of his forces.

A similar fate befell the attempts of Wurmser to aid the relief efforts by attacking out of Mantua. His attacks were either too early or too late.

In any event Davidovich after his great success on the 17th paused to wait for news and orders from Alvintczy. By the 21st he realized he was facing most of the French army and that morning began to retreat. Alvintczy who by the 19th was at Olmo just west of Vicenza hearing of Davidovitch's success on the 17th had begun to advance again on the 20th. Alvintzcy was at Caldiero again by the 21st.

In the meantime the French under Bonaparte had caught Davidovich and routed him. The Austrians made it back to Corona and Ala with heavy losses. Part of the reason for the severity of their defeat was the confusion engendered by orders to march and counter march consequent on delayed news from Alvintzcy. In any event Davidovich's forces were played out and incapable of further offensive action.

On the 23rd of November Alvintzcy realizing he was about to be facing Bonaparte alone again retreated from Caldiero. The French worn out themselves did not pursue vigoroursly.

This first advance by Alvintzcy was Bonaparte's closest call in Italy. The balance of forces so favored the Austrians even at the end of the campaign that many commentators believe Bonaparte basically bluffed his way to victory. They believe that Alvintzcy lost his nerve before Verona because of the attacks at Arcole on the 17th not that it was in fact militarily necessary for him to retreat.

I believe this does Alvintczy an injustice. Alvintczy's return to the offense on the 20th even after the mauling at Arcole is evidence of his courage and determination. Davidovich also made repeated attacks despite initial deficencies and in the face of multiple set-backs. That the Austrian generals made mistakes is without doubt, that the failure of the campaign was caused by the personal deficencies of the Austrian generals I do not believe.

Rather the failing was one of an entire system of war. The first failing was the binding of the hands of the Austrian generals on the scene by overly detailed and rigid plans dictated from Vienna. The second major failing was an operational doctrine that dispersed ad hoc clumps of battalions and squadrons in broadly dispersed cordons or columns and required they advance and retreat in pre-determined co-ordinated fashion without reference to the terrain or the speed of communications. As Bonaparte commented the Austrians never seemed to appreciate the value of time.

Before being too hasty to judge one should note that this same system of war had been quite successful against both the Turks (we should never forget it was the Austrians who defended all of Europe against conquest) and against the Revolutionary French in Germany.

It was only against a revolutionary army in Italy commanded by Bonaparte that its weaknesses became obvious.

Note: You will need to cut and paste addresses given into your browser's address line in order to follow them.

Martin Boycott-Brown refers to a set of articles by J.B. Schels for much of the view from the Austrian side of the hill. These articles were written in the Austrian Military History Journal ( Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift or OMZ) that was first issued in 1808 and which is still being published. See https://www.oemz-online.at/

They're in German and I don't speak German but in hopes there might be tables or some such formatted data I could piece together I located copies of these articles online. Unfortunately the main piece of information I managed to gather is I really can't read German. However, in the hope that some of you do and that this might be helpful I'm giving the location of these articles below. If anyone could translate them and see their way free to sharing that'd be great.

Turns out the digital collections of the New York Public library includes some maps with locations otherwise have had a hard time with.

See https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6d1df996-97eb-f6b6-e040-e00a18063a3f which accessed on 2017-12-27 as an example.

Some of the spelling of placenames in Bonaparte's correspondance does not match what you'll find on a modern map in English or Italian. For instance:

This variance in spelling matters because many placenames are very similar. In fact some are exactly the same (multiple Pradellas, Rivaltas, Ospedallettos, Gazzos, etc) and can only be understood in context or by long winded elaboration. Many names are used in a shortened form, that is "Desenzaro" for "Desenzaro del Garda", "Peschiera" for "Peschiera del Garda", "Vallegio" for "Vallegio sul Mincio", "Rivoli" for "Rivoli Veronese", "Castiglione" for "Castiglione delle Stiviere", and so on.

There is also some variation in the names of people