An overview of French Revolutionary and Napoleonic War Cavalry at the tactical level.

Cavalry dominated the battlefield in the Middle Ages, from roughly 500 to 1500 AD.

Infantry armed with pikes and firearms then started to change that, in Western Europe at least, starting around 1500. By 1700 infantry armed with the flintlock musket fitted with a socket bayonet had completely displaced cavalry as the dominant arm on the battlefield. Even heavy cavalry could not break trained infantry with good morale, in formation and prepared for its charge anymore.

This does not mean that cavalry ceased to be useful with the coming of the eighteenth century.

At the very least cavalry remained indispensable in the scouting and pursuit roles.

Moreover infantry wasn't always well trained and didn't always have good morale. Even when it was, and it did, it could be caught out of formation or otherwise unprepared. Under such circumstances cavalry could prevail even in pitched battle.

Finally unusual events, fortunate or unfortunate depending on your point of view, do occur. A horse is killed while charging and falls among the ranks of infantry breaking their formation. Rain leaves musketmen unable to fire allowing lancers to approach them closely and use their superior reach to pick the infantrymen off.

Cavalry was not just very useful in scouting before battle, and in mopping up afterwards, it could not be discounted during it. This remained true up to and including Waterloo.

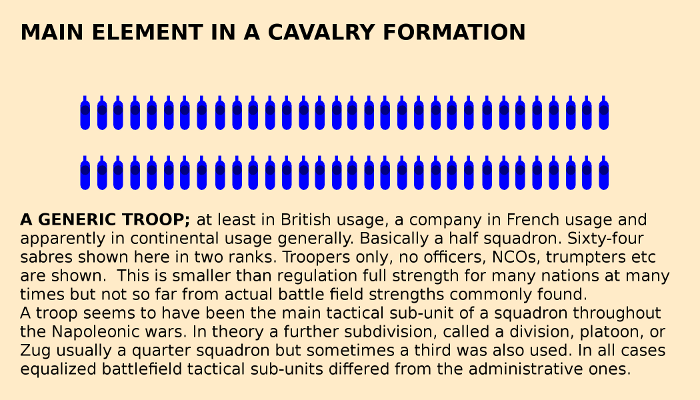

The basic tactical unit of cavalry in this period was the squadron. Generally made up of 90 to 200 man (trooper) and horse (mount) pairs often called sabres the specific size of units even at full strength varied by nation and period. After a campaign began squadrons started to dwindle in actual size of course.

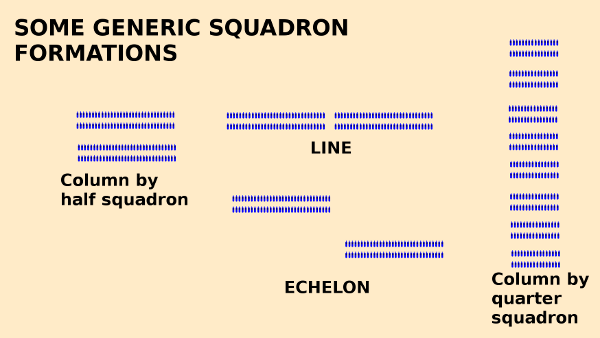

As shown above squadrons deployed in two ranks and their main tactical sub-unit was usually the half squadron sized troop or platoon. Zugen in Germanic usage.

For all that the squadron was the main tactical unit on the battlefield cavalry would often deploy as regiments made up of up to five squadrons. Regiments were also the main administrative unit.

The Prussians in particular appear to have diverged from the usual practice in that they would maneuver in regiments with squadrons as the main tactical sub-unit(usually four to a regiment). Their squadrons had quarter squadron sized units, they called "Zuges" as their main tactical sub-unit.

In order to better handle its variety of quite different tasks cavalry was generally specialized into classes. At the very least into heavy cavalry and light cavalry. Often a third intermediate category of medium cavalry was used.

Heavy cavalry were units called things like cuirassiers, carabiners, the "Garde du Corps, British Household cavalry, "Grenadiers a cheval", Gendarmarie d'Elite, and sometimes, particularily in British usage Heavy Horse or Heavy Dragoons. Heavy cavalry were big men mounted on big horses intended to be used on the battlefield to overpower other cavalry or wavering infantry. The cuirassiers were named after the heavy partial armor they usually wore. Generally at least a heavy breast plate or "Cuirass".

Dragoons, originally mounted highly mobile infantry, were by the Napoleonic period simply another form of cavalry. Sometimes considered medium cavalry, sometimes depending on nationality and period heavy or light cavalry. The British explicitly had "Heavy Dragoons" and "Light Dragoons". Troops armed with a lance were sometimes considered medium cavalry too. Sometimes called just lancers, sometimes called uhlans after the leader of a famous Polish unit of lancers that provided the template for the unit type. In any event "medium cavalry" was not a hard and fast designation, and seems to have depended on whether units were viewed as being usable on the battlefield. The famous cossacks for instance were armed with the lance but were definitely not medium cavalry. They were superb light cavalry but didn't have the weight or discipline to go toe to toe with the enemy on the battlefield.

Units considered as being medium cavalry tended to have men and horses intermediate in size between true heavy cavalry and true light cavalry.

Light cavalry performed most of an army's scouting and screening tasks. Nimble endurance and flexibilty were the traits they needed. They were slight men on fast but smaller horses. They tended to harass and scout rather than to charge and break.

Hussars were the most common type of light cavalry. Uhlans were most often considered light cavalry too. Light Dragoons, Light Horse, Chasseurs a Cheval, "Mounted Jaegers", and Chevaulegers are other names suggesting light cavalry.

In addition to regular light cavalry there was irregular light cavalry like the cossacks, tartars, bashkirs, bosniaks, freicorps cavalry, and mamelukes. Of no weight on the battlefield in general, in the pursuit, or in strategic operations they could have considerable influence through raids (especially in late 1812 and early 1813), scouting and harrassment.

As with the infantry cavalry had two main formations "line" and "column". Cavalry did not usually form squares but they did have their own unique formation called "echelon", which can be thought of as a kind of step wise diagonal or refused line. It allowed a regiment deployed in it to hit a wavering foe with a series of squadron or troop sized charges.

The various specialized tasks of cavalry gave rise to a specialized vocabulary.

In particular you'll read of the war of "outposts". Screening and scouting for an army wasn't just a day job. Squadrons and troops of cavalry would often camp and keep guard in advance and on the flanks of the main infantry heavy army. So that it could not be taken off guard and to shelter it from enemy eyes and give it some room to maneuver. Very small outposts of less than a half dozen men, sometimes a single individual and his horse were called "vedettes".

With the cavalry you didn't have to train a man to just use his weapons and to keep formation, you had to teach him to ride and take care of his mount. The mount too needed to be taught what was expected of it. Furthermore good mounts couldn't just be conscripted from the local peasants or townsfolk they had to be found and purchased.

Once procured mounts had to be fed. Fed well and correctly if any serious effort was to be expected of them. Curiously horses seem to have been more susceptible to sickening and dying of a bad diet than men. Less able to fend for themselves too.

There are not many Countries that do afford Horses fit for the Service of Cuirassiers.

Good horses in good numbers weren't available just anywhere. There were certain regions that specialized in supplying them.

This could be of strategic importance as in 1813 when Napoleon lost control of the regions of Germany that supplied the mounts for his cavalry.

In general the main horse producing regions were on the northern and eastern fringes of the western and central European heartlands. This put the Prussians, Russians, and Austrians at something of an advantage over the French at least once war became sufficiently widespread and total as to cut off normal commercial trading patterns.

The Prussians, "Germans", French and Austrians all procured their heavy horses for the Cuirassiers and heavy Dragoons from North-West Germany, the regions of Holstein, Mecklenburg, and Hanover.

The Prussians found lighter horses in East Prussia, Poland, and Moldavia.

The Austrians also procured light horses for their Hussars, and Dragoons from Moldavia, as well as Hungary, Transylvania, Wallachia and Ukraine.

Duffy writes that "by far the greater proportion of remounts came by way of contracts which the state placed with expert dealers" and that "The largest horse fairs were in Wurttemburg, Ansbach and Bavaria.". That is to say southern Germany.

Duffy is writing about the Austrians mainly in Maria Theresa's time, but there is no reason to doubt that these patterns continued into the Napoleonic period.

Duffy also writes that in the 1760s "the state established a number of breeding-stations in Bohemia and Moravia" but that the system broke down in the War of the Bavarian Succession and that the Austrians once again had to resort to horse dealers who procured their stock from traditional regions such as Holstein.

The British appeared to be able to provide their own mounts. France produced horses, large ones in Normandy and lighter ones from the Ardennes but not in sufficient quantity to provide for all their cavalry. In addition to large horses from northern Germany and lighter ones from eastern Europe they either bought or captured they also denuded Spain of its horses. Just the same in 1806 as well as in 1813 they found themselves short of mounts.

Even with access to horse breeding regions mounts couldn't be stamped out of the ground instantaneously. Mares are pregnant for a year before giving birth. Mounts of at least five years old were preferred although three year olds might do. Then once procured they still needed training.

As was explained earlier the last decade of the 17th century saw the evolution of infantrymen armed with flintlock muskets fitted with socket bayonets. By 1700 this development had put paid to cavalry's dominence of the battlefield. It could no longer expect to charge and prevail against a trained and prepared infantry unit.

So the first half of the eighteenth century saw an emphasis on the scouting and screening duties of the cavalry. This was epitomized by the adoption of Hussar units by most major powers based on a traditional Hungarian light cavalry used by the Austrians.

It was the Prussians under Frederick the Great mid-century during the Seven Years War that restored cavalry to a decisive role on the battlefield itself.

Massed attacks by Prussian cuirassiers and dragoons achieved critical successes most notably at the battle of Rossbach which saw a French army twice the size of Fredericks decisively beaten.

The restoration of lance armed cavalry, epitomized by "Uhlan" units based off a Polish template, was an even later development but they were increasingly common by the time the Revolutionary Wars rolled around and Napoleon became a fan after employing Polish lancers in 1807.

The French revolutionaries saw horses and the cavalry as symbols of the old regime. Many cavalry officers emigrated. Horse breeding programs started by French kings were shut down. Cavalry was the step child of French armies through out the revolutionary wars. This is not to say professional officers like General Bonaparte didn't see the need for it. Still they mostly had to make do with undertrained penny packets of it.

The powers of eastern Europe all had access to supplies of good horses.

They were also with the exception of the Prussians constantly exposed to warfare with the excellent light cavalry of the steppe peoples and the Ottoman Turks. They learned to answer in kind.

The Prussians who fought the Poles, Austrians, and Russians needs be also learned their lessons in cavalry warfare. The light cavalry of the Austrians kept Federick's battlefield victories from having the full impact they should have.

The Revolutionary Wars saw the Polish state extinguished in 1795. But the remaining great powers in the east of Austria, Prussia and Russia were strong in cavalry both light and heavy.

The Prussians retained a reputation for weight and discipline on the battlefield at least up until 1806.

The Austrians, the original home of Hussar units, had superb light cavalry.

The Russians had good horses and numbers if not finesse.

The British had good horses and good morale.

What they were lacking was discipline.

Also they weren't particularly well trained at least in battlefield tactics, and generally had a amateur as opposed to a professional outlook.

The last was somewhat true of the infantry too, but they at least had a great deal of practical experience to make up for it.

Mainly deploying small armies by sea, supplied by sea, the British couldn't and didn't have the massive cavalry forces of the continental forces.

Wellington is famous for having written of his cavalry that "[t]hey could gallop, but could not preserve their order.".

In fact they had a reputation for wildly charging at anything and never coming back.

To be fair Wellington didn't have much cavalry until later (1811 or so) and it was not well suited to the sort of tightly controlled micro-management he favored.

As early as the Salamanca campaign it seems to have done good service in the pursuit.

At Waterloo it's intervention against a major French attack proved decisive.

At Marengo in 1800 too, the French cavalry small in numbers and previously something of a step-child, proved itself by helping land the decisive blow.

Napoleon used the years of relative peace between 1800 and 1805 to build the French Army the cavalry arm it'd previously been lacking.

It proved a nasty surprise to both the Austrians and the Prussians in the years 1805 and 1806 respectively.

It continued to prove itself in Poland and East Prussia in 1807 against both the Prussians and the Russians.

Poland was hard on the cavalry, the logistics were horrible, but Poland also provided excellent mounts and troopers to swell the French army. In particular the Polish first directly provided Napoleon with lancers than trained French recruited cavalry units how to wield the weapon.

Polish cavalry proved famously effective in Spain in 1808.

The French cavalry arm continued to prove effective in 1809 in the battles against the Austrians. It acted as a well trained component of a combined arms team. Modern warfare had arrived. For the next hundred years cavalry would be a part of that.

"Our horses have no patriotism. The men will fight without bread, but the horses won't fight without oats."

In Russia Napoleon lost an army.

An army of men, but also one of horses, and the horses proved harder to quickly replace.

The victories Napoleon eked out at Lutzen and Bautzen in the spring of 1813 proved indecisive. It is a common opinion, and plausible one, that this was due to his lack of effective cavalry to follow up on the battlefield successes of his infantry and artillery.

The French problems continued in the Autumn of 1813. Napoleon's new armies were defeated and forced back to France. Bad operational intelligence and an inability to capitalize on hard won battles were likely decisive. A better more numerous cavalry would have helped with that.

The winter warfare of early 1814 in France also saw Napoleon without the cavalry he could have used.

Having been defeated and abdicated in 1814, Napoleon made a famous comeback in 1815.

It ended at Waterloo.

The cavalry the Bourbons had reconstituted proved useful especially early on in the campaign.

At Waterloo itself it severely punished the British cavalry in the aftermath of a charge that broke a major French and infantry attack and ended with the British among the guns of the main French artillery battery.

Sent in during the afternoon to finish off Allied infantry Ney thought was wavering it famously failed to break the squares of British infantry.

In the end it was the Prussian cavalry that relentlessly pursued the broken remnants of Napoleon's last army.

Cavalry was not the dominant arm in eighteenth century or Napoleonic warfare.

It was difficult and expensive to use.

Used properly it repaid the effort and expense that went into it.

By providing intelligence to a commander, and denying it to his opponents it multiplied the effect of his maneuvers.

In battle it could charge home to provide the final decisive blow.

The battle won, the cavalry was the arm that procured the fruits of victory.